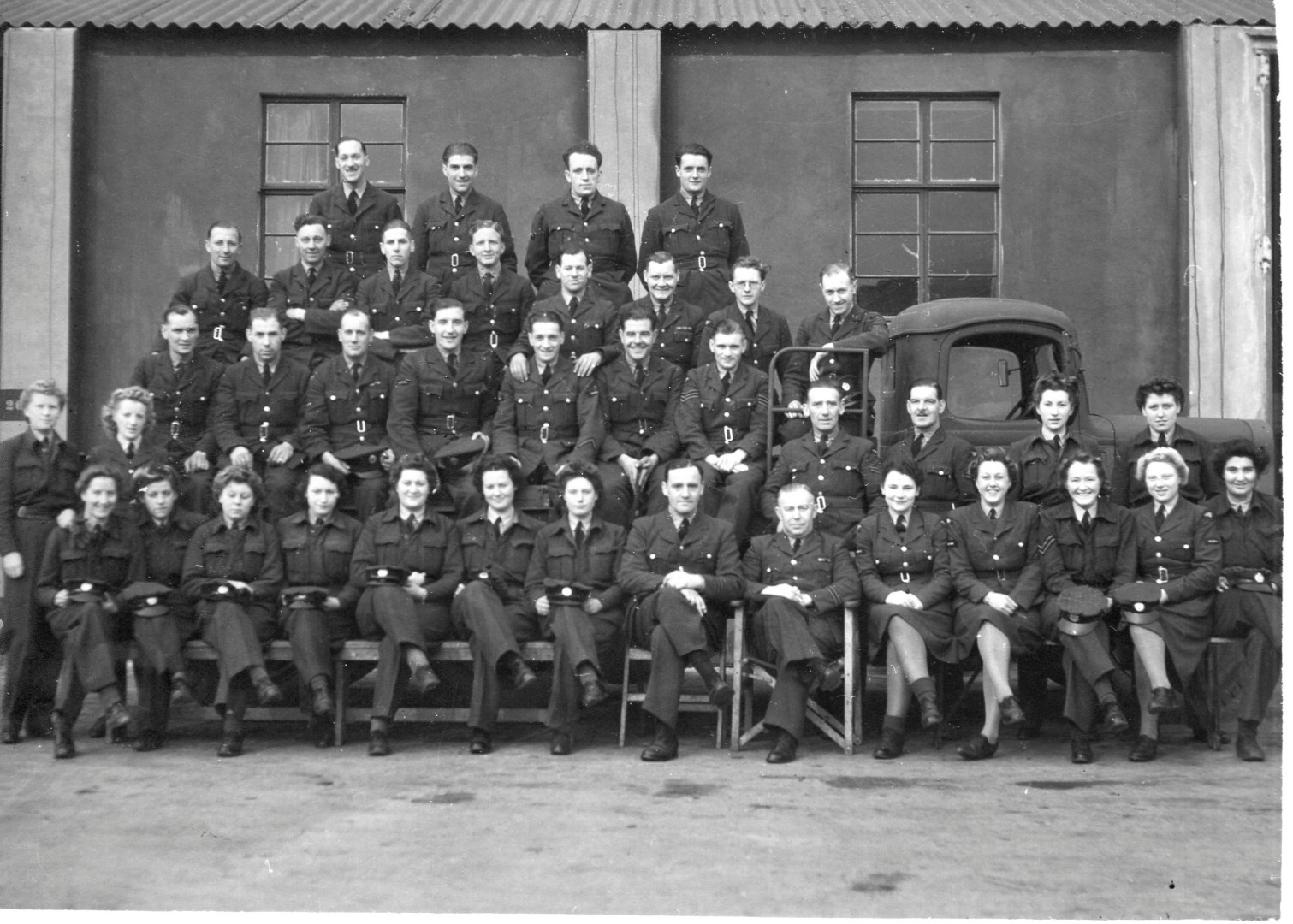

Members of No 11 OTU, Bomber Command, at Westcott. Anne is seated in the bottom row, second from the right. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

L.A.C.W. Anne Crone (457347) (1921-2014) (Later Anne Brinsley)

Memories as an RAF Driver

Kindly provided by her daughter Philippa Werry.

I decided to join one of the Services but which one? Not the Army – I ruled that one out. Toyed with the idea of the Navy but then applied to the Air Force. By 1942, choices were limited and the one that appealed most was being a driver. I thought I would get a chance to drive all over England, never dreaming that I would be driving Air Crew on an Operational Training Unit, and driving a variety of vehicles, including cars, trucks and coaches.

It was August 1942 when I went to Blackpool to get my uniform (be kitted out was the phrase). Everything was blue, including the blouse. A heavy greatcoat for winter with brass buttons which had to be polished! Dress uniform, a tailored jacket, again with brass buttons, and skirt. A bomber jacket and trousers for general driving usage and heavy shoes and stockings. And of course the hat, again with a badge to be polished.

I had my 21st birthday, sharing my cake with some strangers, sitting on an Air Force bed in a large room and probably eating the birthday cake my Aunt had probably made and posted to me. Imagine my surprise and dismay, when after they had left, I discovered that one of them had taken a pair of my pantyhose, I never did discover which one.

At Blackpool we had medicals and when they had decided you were fit enough, training began. We were taught to drive by The British School of Motoring but also had to learn all about the insides of a car (called theory) just to make sure you knew where the dip stick was and where to top up the oil or how to change a wheel, amongst other things. The driving training was a lot of fun – six weeks of it – some people didn’t pass, but there were some hair- raising moments for those who did. Altogether the course, including theory, lasted 10 to 12 weeks.

I had a friend called Joan, who was very nervous and I suspect made the instructor nervous too. There always had to be two of us in the car with the instructor. He had a nervous habit of repeating things = “put your foot on the brake, put your foot on the brake”. I don’t know which of the three of us was the most shaken by the time her turn was over. She invited me home to Edgbaston for a weekend. I was sad when Joan decided to apply for a medical discharge from the Air Force as I felt we could have been really good friends.

When people think of the War, they usually have sad memories, especially if they have lost someone, but there was fun to be had and in London, although there was so much bombing, it seemed to bring out the best in people – and they could always find humour in the most trying situations. We had lots of fun at Westcott. I think the main reason was that we were an Operational Training Unit – the last stage for the crews before going on to Bombing Operations, and we always expected the crews to come home after their flights. They, in turn, must have been more relaxed than if they were flying out to bomb Germany.

We had lots of different nationalities from all parts of the Commonwealth: Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, and from Europe we had Poles. Our main duty was to pick up the crews from their billets (living quarters) and when they had boarded the truck or bus (depending on how many crews were flying), we drove them out to where the aircraft was waiting for them on large circles of concrete leading off the perimeter called a parking bay.

Of all the places I could have spent most of my war service, I think I was lucky to have been posted to Westcott. I had just turned 21 and most of the people at the Air Force Base were young too. Air crews from all over Great Britain, Canada, Australia, Poland, to name some – in the transport section we were all young, too, and there was a spirit of camaraderie amongst us all.

The air crews were in their final stage of training before going on full operational duties. They flew in Wellington bombers and would then move to Lancasters for the bombing raids over Europe. But that was still to come and they were a happy crowd without the tensions of the final stages of their training. This was BOMBER COMMAND (11 O.T.U).

Members of No 11 OTU, Bomber Command, at Westcott, c. 1942/43. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

Members of No 11 OTU, Bomber Command, at Westcott. Anne is on the second row from the front, second from the right. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

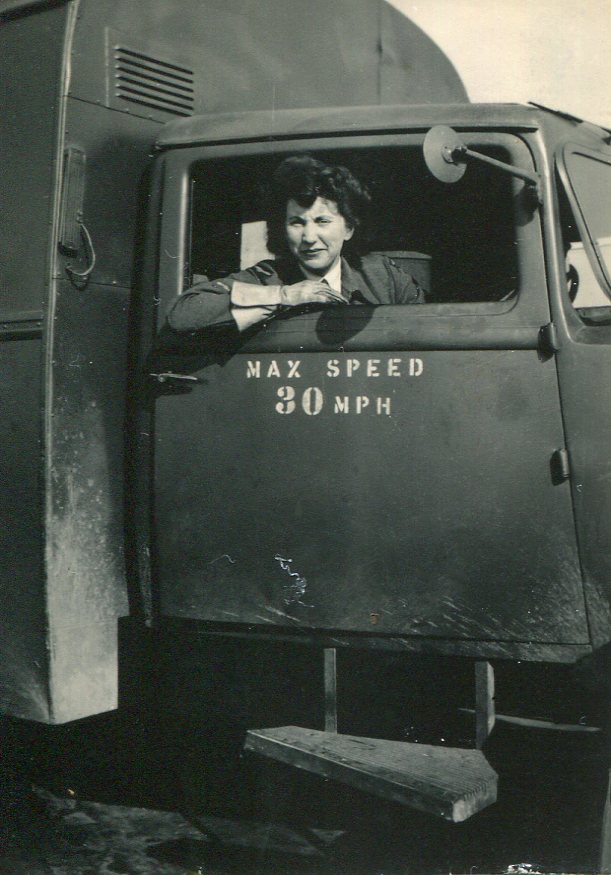

Anne pictured on the left during the Second World War. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

Our driving training over, we were then in a position to drive almost anything from cars to coaches – the latter for when we drove to the living quarters of the crews who were waiting to be taken to the airfield. Depending on the size of your vehicle, you could pick up one or two crews. Their flying gear was very bulky, so they took up quite a lot of room. They always wanted to know the name of the driver so we became familiar with them all and there were many comments about our driving, especially as the coaches or trucks had very noisy gear boxes and we had to double de-clutch whenever we had to change gear. A quiet gear change would often bring applause and you can imagine the comments if you missed one and had to rev up again.

We drove out to wherever each aircraft was ‘parked’ and left the crew there and it would be hours before we saw them again when their flight was over. Sometimes they flew during the day and sometimes at night, consequently we worked on shift duty. If we were on night duty the kitchen staff would make sure we had enough food to prepare a cooked meal during the night. We had a wood burning stove and used to cook on the top of it – mostly fried food which would be frowned upon now, but tasted good at that time. The air crews had their own ‘Mess’ where they had breakfast after debriefing. They had time-out just as we did and there was always transport provided to take us to the local station for the train, usually up to London and to meet the train at the end of the day and take us all back to our sleeping quarters.

Talking of sleeping quarters – well how shall I describe these. They were somewhat of a shock when one first saw them and realised that this was to be your home come fine or wet weather, snow or hail. They were made of corrugated iron with one small wood-burning stove in the centre. I am trying to think how many of us slept in one hut – possibly about 8 each side (so 16 in all). We had iron bedsteads and the mattress was in three parts (called biscuits). We had to stack these and the blankets and pillows each morning in case there was an inspection. The hut had to be left in a very neat state. At that time smoking was not considered to be dangerous, so quite a number of the girls smoked. You can imagine the atmosphere with a heater burning. Our ablutions (a name given to the place where you washed or showered) were some distance away – say the distance of a small field. One learned to bathe quickly and hurry down to breakfast which was in another building called the ‘Cook house’. Owing to food shortages some foods tasted rather weird, e.g. scrambled eggs made with powdered milk.

Our worst scenario was driving when it was foggy. On night duty I had to drive out and pick up a crew which was landing and the fog had come down. I could scarcely see a few metres ahead of me. Suddenly out of the mist came an aircraft taxi-ing to its parking bay. To my horror, I realised I had taken a turn too early and was on the runway instead of the perimeter. I had to swing hard left to avoid the wing. No harm done but just as well he was not taking off – he might have taken me with him!

Anne Crone during the Second World War. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

On night duty we used to be given supper by the cooks in the kitchen. Bad habits developed as often they provided bacon and eggs and potatoes, and we only had the top of a wood fired room heater to cook on. We used to call them our fry-ups. We would be on duty from about 8pm until 6am when it was night duty. There were other things of course. Officers to drive to other camps – sometimes one had to stay the night. It was a good way to see parts of England although Bomber Headquarters was the best place for long trips in ordinary cars but I will come to that later.

Westcott was a village in southern England, not too far from Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, and not too far from London by train – close enough to go up for the day. The countryside around Westcott was lovely. Small villages with village greens, thatched cottages and the inevitable small pub which was the meeting place for relaxation of the Air Crews. We had dances too at one of the villages which had a large hall. English pubs were cosy places where one could take one’s time and sit around log fires. During the war, I suppose was the time when women joined men there, but when I was young it was frowned on for women even to be seen in a pub.

I really think I was lucky to be posted there. The amazing thing was that I should meet Noel there, who incidentally had joined the New Zealand Air Force in August 1942 and I had joined the Royal Air Force in August 1942. From two different countries our future emerged, although we did not know it then. Perhaps our stars collided.

Another exciting thing happened – two, actually. The first was the arrival of United States troops (an Infantry division) who set up camp not too far away from us. They were there for only a short time but had lots of trucks and the men even acquired bicycles if they wanted them. They were invited to come to our dances and we to theirs. It was all good fun. They were mostly from North and South Carolina. Just as quickly as they arrived they disappeared. It was D-Day and they were on their way to France.

The only evidence that they had been there was a few bicycles left in a field or in a ditch alongside – signs of a hasty departure. One of the boys I remember was called Frank Pruitt, from South Carolina. He wrote me one letter from France but I often wondered if he survived as there were massive casualties from the first landings. We were just getting to know them and then they were gone.

The second was the return of Prisoners of War following V.E Day (Victory in Europe) Day. Some of them landed at Westcott Airfield and it was quite an emotional time. Most of the men were thin and disheveled and jumped out of the aircraft and kissed the ground – they were so pleased to be home. We had a special fumigation area which was their first port of call before they eventually got clean clothing and had a good meal. Then they were interrogated. There are some days which one never forgets, and this was one of them.

There were great celebrations all over England and especially in London where crowds gathered outside Buckingham Palace. As far as we were concerned the war was over in Europe but it did not end until the Atom Bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and then we had V.J Day (Victory in Japan). Another celebration of course!

My final posting was to the Headquarters of Bomber Command in High Wycombe – the Residence during the war of Air Chief Marshall Sir Arthur Harris (BOMBER Harris, as he was known). No flying activity from here – strictly a Headquarters and the place where decisions – sometimes debatable – were made. Who will forget the “Thousand Bomber Raid” to name just one. This was, for me, a different kind of adventure. Our duties mostly involved driving Officers to different parts of England. We had very nice cars instead of the heavy trucks and coaches of Westcott. This was the place where I met Nan Walker (eventually Nan Myles) and we have enjoyed a lifetime of friendship. Neither of us expected at that time that we would eventually settle in Australia and New Zealand. Some of the people I was asked to drive were most interesting. One day I was sent to collect “Bomber Harris” – can’t remember where I took him – I must have been so overcome to see this man in resplendent uniform who had been so involved and had to make such big decisions.

Photograph from Bomber Command HQ, High Wycombe, 1945. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

Then there was an American Officer who was black. At that time, in England, believe it or not, it was unusual to see couples of mixed colour – there was even an almost racist feeling about it. We stopped, for morning coffee and doughnuts (my suggestion) at a café on the way north and the expressions on the faces of the other people in the café were rather startled. He was incredibly courteous, something I could not always say about our own Officers but they were the exception.

We had more time off too and I used to go up to London with Nan to see her family who lived in Kensington – they were living there during the war and during the air raids had a fire bomb land on their roof. Fortunately, they were able to put it out. To be able to go up to London and to know that the bombing had ceased was wonderful in itself. To feel the excitement of a war-free England and wonder what lay ahead in the future.

I had one more short posting to Norfolk (a town called Thetford) but this was just a Unit from where we were finally provided with all the things we would need to prove our discharge from the Air Force.

By then it was 1946 and I had been in the Service for almost four years. Time to say goodbye and move on.

Anne standing in front of a painting of an RAF Driver. Copyright Anne Crone/Philippa Werry

Many thanks to Philippa Werry for supplying this article. If you have an airfield story please contact us today.