Supporting notes to ATA diary extracts: January – August 1943 and January – March 1945

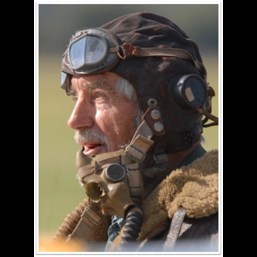

Peter Garrod before a 2015 Spitfire flight. Taken by Alistair Garrod, courtesy of John Webster and the ATA Association.

General:

These notes are copied direct from those handwritten in two pocket diaries approx 4ins x 3ins and were simply intended as a personal record of a particular time of special interest in my life. With one or two exceptions, they omit entries covering periods of leave but where included are only to give some indication of how leave was spent as a matter of interest of life at the time. At the foot of most entries, some explanation is given in brackets of phrases, people, places and abbreviations in the text.

Piloting discipline and general behaviour in the air: I was astonished at what I found, when reading these diaries after retrieving them from obscurity amongst other documents and items forgotten for some 60 years. Aerobatics were forbidden in ATA, and pilots were naturally expected to hand aircraft over at the end of each flight with the minimum of stress on airframe or engines. “ATA Cruise” in the handbook laid down the desired power setting to be used, and straight and level cruising flight to the destination was to be the normal practice. Yet I clearly flouted these instructions almost continuously by indulging in aerobatics – principally by rolling but occasionally by looping – on the majority of aircraft with a natural aerobatic ability. I also “shot up” both ground “targets” and other aircraft whilst airborne, although “shooting up” in most instances involved – I now believe – no more than a fairly low level pass or flyby.

Three questions arise in consequence:

1) How did I learn aerobatics?

During my Class 2 conversion my American instructor on the Harvard – Tex Pierce – after going through stalls, spins and their recovery told me that “there was a young aerobatic pilot in me just bursting to get out”. He also believed that every properly trained pilot should have had some training in aerobatics. Through a sequence of stall turns; heavily barrelled rolls; straighter rolls; half rolls off the top he gave me a basic confidence in aerobatics. For this I was to be very grateful for enabling me to recover from two incidents later which might have had a serious consequence. (See appendix at end of these notes)

2) Were ATA unit Commanding Officers aware of this practice?

Peter Mursell, CO of Ratcliffe certainly was because he suspended me for three days without pay for rolling a Hurricane over Ratcliffe on 14th May 1942. I believe that I was very lucky not to be dismissed. Gerry Stedall, CO of Cosford must also have known because all of the twelve or so pilots in this small unit would have seen me doing aerobatics when up with them and this must have come up in general conversation. Victor Cook CO, of Sherburn and Ken Gill – No 2 – must also have been aware. As recorded in these diary extracts, I was “challenged” to give an aerobatic display in a Wildcat actually overhead Sherburn. I was not censured for this – nor reprimanded.

3) Did other ATA pilots also indulge in aerobatics?

I have to respect names and reputations here and for those no longer alive. I can confirm seeing several other pilots performing manoeuvres which were certainly not “straight and level flying” and there is one well known photo of a Vickers Warwick flying inverted and clearly attributed to a named pilot. There were also pilots who I witnessed persistently flying at much higher power settings than “ATA cruise”. Then there is the practice of flying above cloud with climb or descent through cloud and on instruments. ATA pilots were not given formal instrument flying courses and were expected to maintain visual contact with the ground at all times. But I know that many of the more experienced pilots did not conform with this (including me!). There was a Link Trainer at White Waltham on which I spent a few sessions, and another at Cosford. I believe that most more experienced ATA pilots would enter partial cloud cover, well above ground levels, to practice instrument flying. Other pilots would complete most of their cross country flights at very low altitude as a preferred method especially over the sea or open country. (Those who took part in flying over occupied Europe after D day – of which I was one – were given specialised drills and instruction; dinghy drill and ditching procedures; use of VHF radio and homing procedures; and instrument flying. Pilots were given personal call signs; “Ferdinand”, plus a number – 61 in my case. Our parachute cushions were replaced by (knobbly) dinghy packs)

There are several references throughout the diaries about “quality” of landings. Hugh Kendall, a pilot at Sherburn and later a test pilot with Miles, Handley Page and Britten Norman, had a keen interest in the vagaries of pilots performance eg; why did we seem to have “off days” when we appeared to have no difficulty in achieving smooth, well judged touch downs, or, on other days made clumsy and untidy ones. We kept notes and compared them, quoting any possible reasons that we could recall. Also what was it that, in the particular case of ATA, compensated for the vastly different height of sight line for a pilot of a Stirling compared with that of an Auster. ATA pilots were quite likely to go straight from one to the other. I also joined Hugh in some experiments in high altitude flight without oxygen, with some alarming and – if consequences were not so serious – rather hilarious results. I was the “safety pilot”, in the other aircraft, to warn him of apparent loss of normal behaviour.

Appendix a) John Shirley

His death is recorded in the August 1943 entries. He was a fine friend, who saw me into SherburnDonibristle. I cannot now recall the verdict of the Accident Committee but a Fleet Air Arm officer told me that there had been incidents where the sliding cockpit hood had become partly detached from it’s rails, then collapsing inwards incapacitating the pilot.

Appendix b) Value of aerobatic training

There were two incidents:

Firstly, flying a Hurricane in bad weather and following a railway line that disappeared into a tunnel. I turned on to a reciprocal but then entered low cloud very close to the ground. I pulled up into cloud and, on referring to my instruments, found them to be unserviceable with the artificial horizon toppling. What manoeuvres the aircraft did for the following few minutes I shall never know. I emerged below cloud at low height above ground, semi inverted in a shallow dive. But for my aerobatic instruction I doubt if I would have so instantly recovered – by rolling – to level flight.

The second was also in a Hurricane. Although I presumably tried the controls for full and free movement before take off, I found that after a short period airborne, the control column would not always fully centralise after applying aileron – sometimes only doing so after applying nearly full aileron first. Something not fully visible seemed to be fouling the base of the column. Landing would have been hazardous. After some thought, I decided to roll the aircraft and hold it inverted temporarily, whilst “stirring” the column. I opened the hood as I did not want any possible loose object to drop back into the cockpit on rolling out. The result was successful; a sizeable unidentified object flew past me when inverted, clearing the cockpit, and full aileron movement was restored. The only problem to follow was that I had lost the evidence and I could not make an effective complaint against those who had inspected and passed the aircraft for fight.

In both these incidents I was very grateful to have had some aerobatic instruction.