1994

Bert Brown, the sole survivor of the crew of WL-U, died of cancer in his home town of Wetaskiwin, Alberta. Bert’s parents were so grieved at the thought of having lost both sons in the war that his father sold his interest in the car business. They must have been overjoyed that Bert survived but the war had left an indelible mark on the family. Not only was Bert’s brother dead but his uncle was also killed in Italy with Canadian Forces. Bert worked at a variety of jobs and became the Fire Chief of the town in 1980. As recalled by his son-in-law, Bert never spoke willingly or in any detail about his wartime experience or the crash of WL-U. He only explained that the plane was blown out of the sky so his family assumed that it had been shot down. Bert never did reveal to his family the details of the flight he recounted to a military reviewer shortly after the crash. Most would agree that it is impossible to fully empathise with someone who has had to carry the burden of survival when comrades are lost. One thing Bert kept from the war was a photo of the crew posing in front of a Hallie. It was a memory that he couldn’t put aside and at the same time didn’t want to forget.

Janzen Lake

The Province of Saskatchewan honoured their armed services personnel who died in WWII by naming natural features in the province after them. Lakes, islands, bays, rapids, creeks and peninsulas in the north of the province bear the names of their fallen. In most cases these are pristine natural features that remain virtually untouched by humans. No more fitting tribute could be given to these soldiers, sailors and airmen who died to relieve the world of the oppression of man’s tyranny. Janzen Lake is in the north-east corner of the province, to the east of Lake Athabaska and just below the 60th parallel.

May 2003

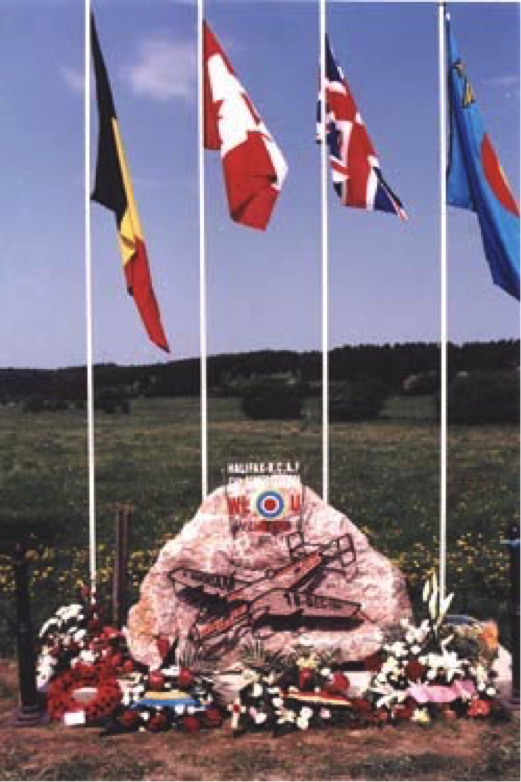

It was an enjoyable spring day in Belgium. The air was warm and there was a hint of rain in the air as the afternoon grew older. A group of about 100 people gathered on a quite country road outside the town of Couvin to unveil a stele honouring six young fliers who died when their bomber crashed at this site 59 years earlier. It was a moving and emotional time for the relatives of the fliers who were present and it was a time of reflection and gratitude for the local Belgians who attended.

The memorial

Following the ceremony at the crash site, the group attended a reception hosted by the Burgmaster in an restored farm building in the centre of Couvin. Gifts were exchanged and it was an opportunity for everyone to meet and socialise over food and beverages provided by the town. For the relatives of the fliers it was a time to speak, first–hand, with locals who either witnessed the crash or lived in the vicinity at the time. It was an emotional experience that was heightened by the difficulty of communicating in French but the bon homi was overwhelming and the friendship genuine.

The ceremony was the result of the persistent efforts of Hector Maurage, a resident of Couvin, to identify wartime crash sites in the area and have steles (small monuments) erected to honour the Allied fliers who perished. For Hector it has been a long and dedicated pursuit.

Margaret McIntosh, Leslie Green, Hector Maurage and Joanne Hart

Also responsible was Leslie Green, of Weston-Super-Mare, England. Leslie’s mother was a cousin of Harry Pearce and Les grew up hearing the story of the crash. Wanting to know more of what happened, Les pursued British military records and on one of his trips to the continent made a side trip to Couvin to try to find the site of the crash. He was fortunate enough to meet Hector Maurage and from that point on, a team had formed to aggressively pursue the goal of recognising this site. Leslie tirelessly tracked down information on the crew and was able to contact Margaret McIntosh, the sister of Alex Divitcoff and Joanne Hart, the niece of Jim Parrott, making possible their attendance, along with his at the ceremony.

December 2003

The crash of WL-U was a single event in the course of a great war that took many millions of lives. By itself it did not have any measurable effect on the outcome of the war. The death of six young men in a plane crash was not significant enough to make headlines or catch the imagination of the public. But for six families spread out in communities from Toronto to Vancouver, the clippings they cut out of the newspaper in order to save a short, one column notice and perhaps a photo of their son or husband it would not have been more devastating or poignant had it been the whole front page.

These families never got to hear the thunder of a thousand Halifaxes and Lancasters flying off overhead to bomb the enemy. They didn’t see their towns bombed and their neighbours die or have their homeland threatened by invasion. Their war meant sending loved ones away from a safe and hospitable environment to a foreign land to risk their lives for someone else’s freedom. It was the ultimate act of charity and in this case, sacrifice. Curiously, the families retained these newspaper clippings as their most tangible evidence of this sacrifice. They were more personal than the small pins provided by the government.

The monument in Couvin, for the first time, makes a significant, lasting and appropriate recognition of this loss. It symbolises the thankfulness of the Belgian people just as it symbolises the personal loss to the families involved. May these men now rest in peace knowing they are not forgotten and that the significance of their sacrifice has not diminished but grown with time.

The memorial