18 December 1944, 0220 hrs

The four massive Bristol Hercules radial engines crackled to life with a thunderous roar and settled into a teeth rattling warm up as WL-U stood poised on the taxi runway. The crews of the eleven aircraft that were lined up for take off tried to settle their emotions and make final preparations. It was one of those times of personal crisis when significant events in a person’s life can be recalled in brief flashes. Perhaps this happened to Jim Parrott despite his best efforts to focus on the mission and bring to bear the three and a half years of intensive training he had received. This was to be his fifth sortie over enemy territory on a bombing mission. Each time he had the same crew with him and there was a comfort level in knowing each of these men as well as he did. Everything had happened quickly since he was put on strength in the squadron on the 25th October, a few short months before.

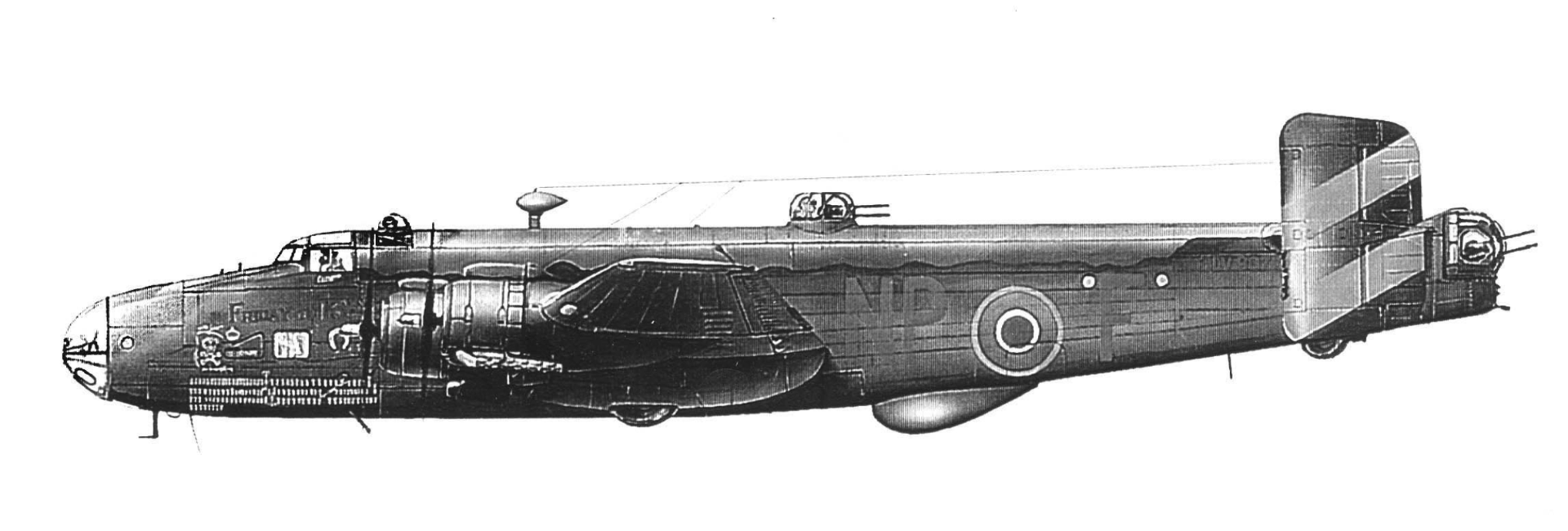

Profile of a Handley Page Halifax

The first week of November was spent in the sick bay at Croft because he had twisted his knee while on a flight and aggravated an old injury. Once the swelling was down and he had good function again, the training flights were resumed to hone their skills in preparation for the big day when they would do their first mission together. It was not far off! On 16th of November, Bomber Command had been asked to bomb 3 towns near the German lines which were about to be attacked by the American First and Ninth Armies in the area between Aachen and the Rhine. They were to be one of the 1,188 aircraft sent to attack Duren, Julich and Heinsburg in order to cut communications behind the German lines. Their particular target was to be Julich but after getting away to a good start at 1236 hours, they had a problem with the inboard starboard engine before they could reach the target area. The oil pressure had dropped to the danger level and the water temperature had risen to a level that threatened a fire if they were to continue. According to procedures they had to turn back and jettison the bomb load over water before landing. They had been in the air for a little over three hours and were disappointed that they had to abort their first combat mission. They didn’t have long to worry about it; however, as they were in the air again on the 18th. This time they took off at roughly the same time and headed for Munster as part of a 479 plane raid. Everything went according to plan and they were able to bomb their target from 17,000 ft using the red and green sky markers that had been set by the Pathfinders. There had been too much cloud to assess the accuracy or effect of their drop. The bond between the crew grew that much stronger knowing that they had done their job well.

Three days later on the 21st they were in the air once again headed toward Castrop-Rauxel in “Happy Valley” as the Ruhr was sarcastically called. Takeoff was at 1655 hours and this was the first time they could put all their night flight practices to use. It was a very busy night as there were a total of 1,345 sorties flown by Bomber Command. They were one of 273 aircraft that were allocated to bomb an oil refinery at Castro-Rauxel and the mission had gone well. They were over the target at 1904 hours at 18,000 feet and the weather was clear. Again they used the red and green markers for alignment and were able to see one large explosion with dense smoke as a result of the bombs they dropped. He remembered marking in his log “Good Effort”, “Good Trip” after they had returned to Croft at 2231 hours. It had been a long day for them and they tried to ignore as well as they could the fact that in total 14 aircraft were lost on that mission. At 1%, losses were much more acceptable than in the early days of the bombing campaigns, but they were losses all the same.

On November 27th they participated with 290 other aircraft in a raid on Neuss. It was another night flight and they were up in the air at 1655 hours and over the target at 2029 hours. That night their payload comprised 1-2000 lb., 7-1000 lb., and 6-500 lb. bombs. On the return flight the weather closed in and they were forced to land at Methwold instead of Croft. This was not unusual because it was winter and in the north of England and many flying days were lost because of heavy storms and dense fogs. The next day on the 28th the weather cleared and they were able to fly back to Croft. It had been a long haul and they were all tired.

Croft was home. For the Canadians who came from small towns and farms it had a familiar feel about it. In the north of England, just south of the town of Darlington and situated on the North York Moors, it was a long way from the industrial midlands and the more built up areas in the south. The base was thrown together in the rush of trying to significantly increase the capacity of Bomber Command in the early days of the war. The first occupier was 78 Squadron of the R.A.F. in October of 1941 and they had to tough it out under pretty rough conditions that first winter. Their original Whitleys were replaced with Halifaxes in April of 1942 but by June the runways had been so damaged by the much larger and heavier planes that the airport had to be closed down for three months for extensive repairs. The main runway was lengthened from 4650 feet to 6000 feet and made 150 feet wide.

At this time a wire arrestor system was installed at the end of the runway closest to the railway track. Heavy cables were strung across the runway and connected to hydraulic dampers that were buried in the ground in order to catch any airplane that could not stop on the concrete. It was not uncommon for planes to overshoot a runway and come to a successful stop on a railway track only to be hit by a passing train. Too many aircrews were lost this way. All airfields had railways in close proximity for the delivery of fuel, bombs and other supplies. The large quantities required and the heavy weights would have been impossible to move via the road system.